Shadow of The Depression

Extract from The Sunday Times 20 January 1963 Shadow of the Depression: Henry Fairlie.

Shadow of the Depression: Henry Fairlie.

Extract from The Sunday Times 20 January 1963

There cannot surely be many industrial areas in this or any other country more isolated than the Cumberland coast between Maryport and Whitehaven. A branch railway line from Carlisle reaches Maryport first; out of the kind of habit which Dr Beecham is trying to break, the train stops there. Before the war half the insured population of Maryport was unemployed. Today, as a town, it has already died. Its harbour is silted up.

The train then takes you to Workington. If you are lucky you will get through your business quickly and let it take you away again as soon as possible.

Workington when we were there was still a little dazed by its first experience of short time after a sudden and lush boom. Two hours after a Friday night dance big gun, a handful of girls were still sadly strung along the walls, hopefully waiting. “You should have seen it a couple of years ago”, said the licensee of the hotel where the dance was taking place. “You would not have been able to get in through the doors”. But Workington is drab, without any assistance from economic forces.

An aggressive young man jaune Palmer he said pushing his hand into mine came across and introduced himself. His first words were flung in my face, across a paint tankard of ale. “High IQ but no fibre that’s my trouble”. He had been to Manchester University, had returned and worked in the steel mills in Workington, had been on the dull. He beefed at me, with the slogans of the anti hero: “I’ve accepted defeat now he said I’m going to be a chartered accountant.”

But another day he took me round Workington on foot and This is why I will never forget him speaking familiarly and softly of what the place had been. He took me to its churches as if they were cathedrals, it’s parks and its pubs. He showed me his grandmothers house, a farmhouse in her day but now in a close terrace. There’s one thing to be said, these are real places up here in the north. Were they his own words all had he learned them?

Real or not, Workington is ill kempt. It council was more frequently criticised to my face than is usual. It’s housing record since the war usually a fair test has not been convincing. I had found the Robertsons in Greenock I found the Ostles in Workington a working in the Cumberland colliery ‘s from his boyhood until retirement. His memories of the old days of the 30s which was earned by a full six day week arbiter. As colliery after colliery closed between the wars it meant long bus or bike rides to another colliery for those lucky enough to find work in them. “The lowlier would walk”. He muttered to himself but one caught a phrase “worse than penal servitude”.

He was almost as bitter about the present day and could find hardly a good word to say for the local national coal board officials. His son Bob Russell is also in the pits a senior over man. He echoed his father’s sadness at the breaking up of the old mining communities. “Once when you went out of this door you knew everyone and everyone was a minor. Now you don’t know one in 10 and you don’t know what they do for a living”. The Cumberland coalfield is finished. If so there is little other work to be had his daughter Mary left school five years ago at the age of 15. She has worked ever since in the office of the national coal board. At the area office of the national coal board the manager talks about the same problem. Out of an insured population for the whole area of 28,000 the collieries employ about 4000 wagemen and weekly paid stuff. The NCB object is a simple one to produce in this isolated coalfield enough prime cooking coal for both manufacturing and domestic uses to supply the needs of the full county.

The story familiar in other areas is repeated here losses have been very high since vesting day the area is geologically badly faulted which makes it increasingly difficult to develop economical seems and there has been little knew construction.

It has been necessary therefore to contract. Where once there were 24 collieries now there are only six and not all of them will last full top. This contraction has meant that losses have been steadily reduced the aim last year was to break even for the first time. But the problem of the men remains, the manager showed little sympathy for the breaking up of the old mining communities. When they lived closely together like that they tended to be resentful suspicious and conservative. It sounded to me very like any other bosses point of view.

As that cool industry contracts Workington will depend more and more on the Workington iron and steel company and the distinct and engineering company both subsidiaries of the United steel companies limited of Sheffield. Their belching fiery furnaces stand next to each other and they in turn next to one of the remaining active collieries in the district. On this limited patch of ground the prosperity of the whole town depends and that means largely on the school of the few men who control the operations of the two companies.

Mr Tom Sanderson the general manager of the iron and steel company and Mr Laird commercial manager both acknowledge the responsibility which they must accept towards the people of Workington who rely so heavily on them. They are two of the most impressive and enlightened businessmen I have met and they claimed with justice that their company has already proved that it is ready to accept its responsibilities.

At the height of the pre war depression it built a new blast furnace in 1932 and a new steel making works in 1934 in 1936 it installed new coke ovens. Since the war it has spent £11,750,000 on all its installations in Workington, the steel mills and works themselves, the mines and the docks. Mr Sanderson talks a lot about the need for ‘human engineering’ it is an unlikable phrase but it covers a multitude of facilities where boys come learn and still may go away even alas to the Midlands for a job.

With demand slacking in in recent years in foreign markets for its finished products mainly rails steel sleepers and fish plates parts of the works have been seriously on short time for several months of the year.

But with a keenness which seems to mark all its operations the iron and steel company is using its own financial resource is in order to enable underdeveloped countries to purchase from them the rails and sleepers they need so badly. At the same time with all the facilities of the research organisation of the parent company behind it, it is trying to diversify its product as much as possible.

If a town has to depend so largely on the activities of one firm it could hardly hope for a more energetic or enlightened company than Workington iron and steel.

Yet the dreariness is the impression of the town which remains on its doorstep is some of the loveliest countryside in Britain there is the Lake District behind it and the sea in front of it. What a happy and thriving industrial community it could be. The dreariness is perhaps not surprising in first a period of short time which could mean the difference of three pounds five shillings in a man’s pay packet each week and then of unemployment. No perhaps is it surprising that there is no obvious way of overcoming the town’s dependence on one heavy industry however enlightened.

But the acute physical problem remains. If Greenock’s physical handicap is in its cramped site between an estuary and a hill, Workington’s is its isolation from amenities of a large industrial area and its lack of either adequate trunk roads or an adequate railway line to connect it with the rest of the country. Again there seems to be the need for intelligent planning of the whole area from Whitehaven to Maryport.

And again there seems to have been an inexcusable reluctance on the part of the central government and its agencies to use the planning powers which are available to it to encourage the development of the area.

It cannot be right to allow a whole industrial area like the West Cumberland coast to become an industrial slum. A private company has shown what may be done. It is time that public agencies took a hand.

……………………

Extract from The Sunday Times 20 January 1963 Shadow of the Depression: Henry Fairlie.

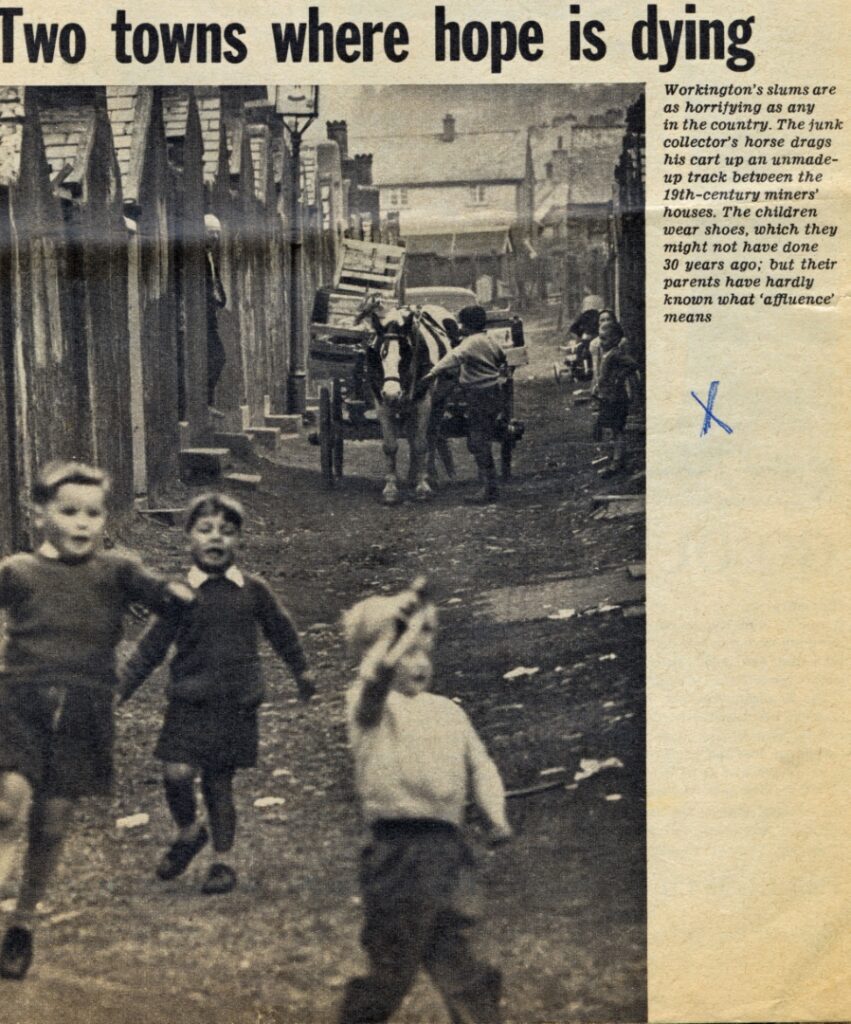

Photograph caption. Workington ‘s slums are as horrifying as any invert country. The junk collectors horse drags his card up an unmade track between the 19th century miners houses. The children wear shoes which they might not have done 30 years ago but their parents have hardly known what affluence means.